The National Ocean Service reports that the ocean contains 20 million tons of gold. But there are no efficient methods to extract it. A few seem to disagree.

A pastor and a diver stole thousands from investors. A Nobel prize winner misses a decimal point. What else could go wrong?

In 1872, British chemist Edward Sonstadt discovered that the oceans contained seawater.

Soon after, in the 1890s, New England pastor Prescott Ford Jernegan was said to have been struck with a fever dream that led him to building his invention. After testing his prototype of a zinc bucket, mercury, and a battery, Jernegan’s Electrolytic Marine Salts Company unveiled his “Gold Accumulator”.

The public was amazed, no doubt thanks to his overzealous pamphlets celebrating the invention. Quickly, Jernegan had investors, over 100 employees, a grain mill, and several “Accumulators”.

To corroborate the success of the company, Jernegan made sure that the first run would be successful. Charles Fischer, a business partner and a trained scuba diver, slipped under the water and salted the accumulators with gold.

The Electrolytic Marine Salts Company was able to hide their scam for some time, accumulating several hundred thousand dollars that the men took for themselves as profit. Eventually, a disgruntled former-colleague blew the whistle and exposed the hoax. Jernegan was a convincing salesman though, as his plant managers kept the machinery running for months after he fled, expecting the process to start working again soon.

A scuba diver of questionable character.

In 1900, London inventor Henry Clay Bull filed a patent for a “method of extracting gold from sea-water”. The process involved adding lime to seawater to lower the acidity and precipitate dissolved ions, including gold, into solid material. Bull expected substantial amounts of gold to collect, but as far as we know, he never tested the idea.

In the 1920s, German Nobel laureate Fritz Haber developed his own method of gold extraction to help repay Germany’s WW1 reparations. Haber and his team of scientists spent a year developing a method that used centrifugal force and electricity.

That is until Haber discovered a rounding error in his initial calculations, and it was discovered that the expenditure was economically improbable. Haber considered the failure of his personal responsibility, believing that he should have caught the error.

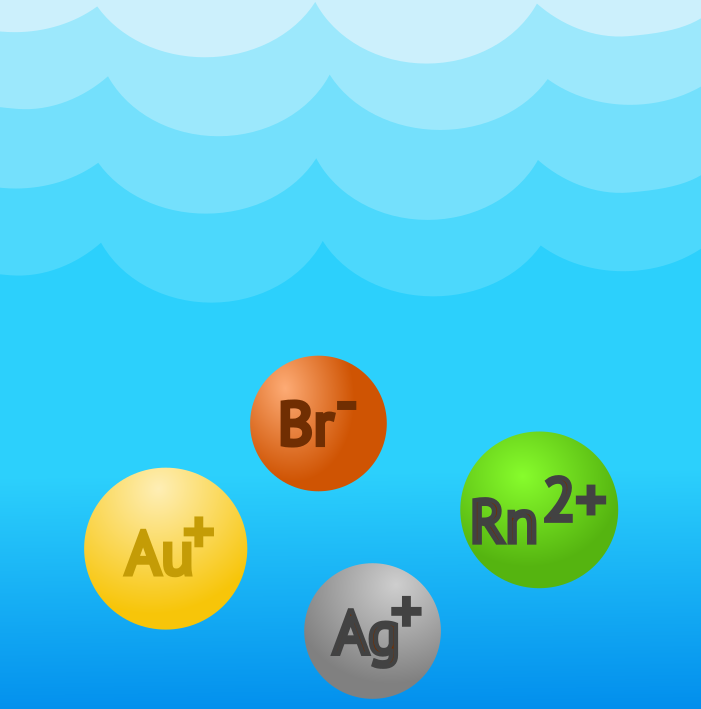

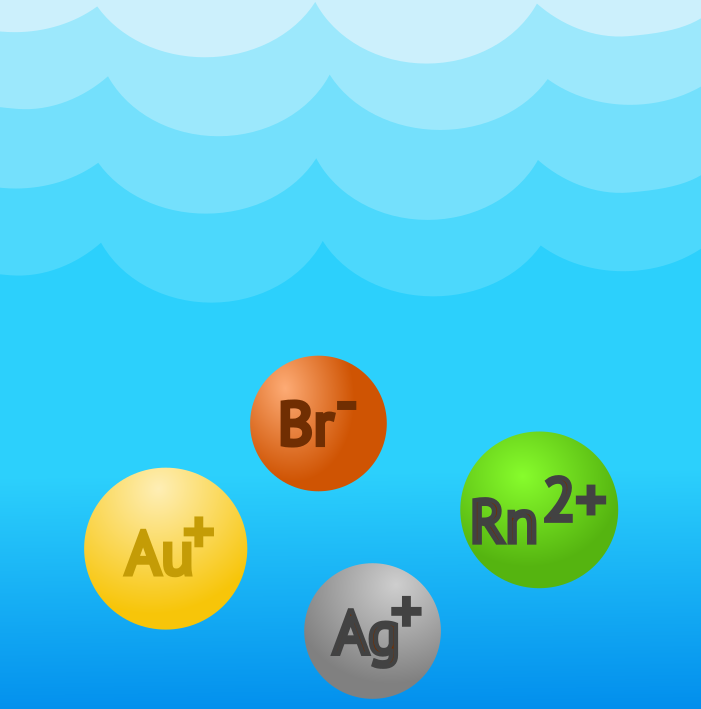

In 1934, a Dow Chemicals plant on Kure Beach, NC reported to the American Chemical Society that they expected to be able to collect seawater gold within a decade. The plant was built to extract bromine from seawater, and believed that advancements in technology would allow Dow to use the equipment for bromide extraction that would collect gold as a byproduct. Other precious metals, such as silver and radon, were expected to be collected by this process as well.

Valuable ions dissolved in the ocean

Dow Chemicals stood behind the claim until it fizzled out. Eventually, in 1941, Willard Dow announced that their expectations had failed, having recovered no more than a pinhead of gold from one ton of seawater“.

In 1942, another patent was filed for gold extraction. Columbia professor Colin Fink had put efforts into his own process of bromide extraction, collecting gold as a byproduct just as Dow had expected. There were no reports of success, and we can only guess as to whether the method was entirely incapable of processing gold, or was not efficient enough to outweigh the expenses.

Could the solution to gold extraction lie within Delftia?

Read part two soon! More recent quests for ocean gold, including one that was featured on Shark Tank!